JB (Julie Buck): Okay, so I am here with my friend Cay and she grew up in Ghana so Cay could you tell me a little bit first off what it is like growing up in Ghana and could you tell me what year you grew up in Ghana?

CS (Cay Smith): I was born and grew up in Ghana. I went to school until I completed my twelfth grade, and then I went to Midwifery School and became a certified midwife. It took two-and-a-half years for that program and I practiced midwifery until I decided to migrate to the United States to get more of the civilized way of doing things, which is quite a bit different from how we do it back home in Ghana, and since then I have been here.

JB: So did you grow up mostly like in the ’60s and ’70s in Ghana?

CS: Yes. I grew up in the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s and then I came to the United

States in the ’90s.

JB: So the culture, at least when you were younger, was it very tribalistic or how was the culture?

CS: It is very tribalistic because I always tell people it’s like part of the country is more traditional, and those who have the privilege to go abroad, mostly Europe. They also have a modern lifestyle. So we combine both and work it out side by side, because those were the traditional mentality and you got to go around them with a lot of carefulness because not everything you tell them they even accept or understand. Right now things are changing because our children have gone abroad and come back home and tell them, well we don’t do it like this anymore. That is not the way it is. So, they are getting the message little by little.

JB: So has the affluency changed in Africa that you can see as you have grown up? What is the rate of poverty? Is it normal to have poverty, because I grew up thinking that Ghana was one of the poorest countries in the world.

CS: Yeah, we have poverty, and then we have the rich and then the middle class. We have both, yeah. We have both, and the poverty is still there. The poverty is still there and in fact some people, they don’t even realize that they are in poverty because that is their life so they are used to it and that is how they live.

JB: What would be a normal traditional African dinner?

CS: Well we do have breakfast in the morning. We do have lunch in the afternoon, and then we do have dinner in the evening, but because of the tribal differences in every tribe in the type of food they eat, yeah.

JB: It’s different.

CS: It’s different in preparation, but sometimes it is the same ingredients, but the way they prepare is different, so we do eat three times a day. JB: So did you grow up in a middle class or upper class or lower class?

CS: I would say upper class because my family on both sides, my mom is mixed with German and African, and my dad is mixed with Dutch and African, so they live both styles. They live both styles. We eat African food most of the time. In fact the Dutch and the Germans, my great parents that married these African women, they love African food, so that’s what we eat. Yeah.

JB: So what are your favorite African type foods?

CS: Oh the pepper is number one. Pepper is number one. We have different types of pepper but they like the hot hot pepper.

JB: What color are the hot peppers?

CS: They grow green. Then as time goes on the color changes to red or brown. In

summer, yellow.

JB: Okay. And you told me once about food for the fufu. Could you explain what that is?

CS: Yes? Fufu is the dehydrated plantain. Okay plantain is the bigger size of a banana sister. I will say plantain banana or cassava. You know, but bananas are sweet and small and plantain grows big and greenish and then it starts to turn yellowish little by little. By doing so the piths become sweet, sweeter, and sweetist. So the green part is dehydrated. Here in America it has been dehydrated and milled into a powder form, and that’s what we use it to prepare the food for. Back home we cook it directly from the tree and we pound it in a mortar and it becomes the same like the ones we use hot water here to prepare.

JB: And it makes kind of like a dough right?

CS: Yeah it is like a dough, it’s like a dough, it’s like, yes a dough smooth and stretchy. Not too soft, but the texture depends. Some like it a little bit tough; some like it medium; some like it very very soft.

JB: So at home how long do you have to pound it to get it the right consistency?

CS: Well when you are pounding the fresh plantain in the mortar, it is a long process. You have to take your time and pound it until it becomes smooth. But as you are pounding it you have to turn it. You have to turn it. You have to turn it to make sure that it doesn’t fall.

JB: Like kneading bread, kind of.

CS: Yes, just like you are kneading flour bread, yeah. And, that’s how we do it.

JB: So you said that you actually had to live with your relatives at age 15. Do you want to explain a little bit about that?

CS: When my parents died I was approaching 16. So I lived with my grandmother and my aunts, and then when I turned 18 I went to the midwifery training school for two-and-a-half years. So by the time that I completed it, I was 21. And then that school had a program where as soon as you graduate, they place you at a hospital or a clinic or anywhere within the country that they need help. They have houses already built, so when you are transferred, by the time you get there your house is waiting for you.

JB: Is it the school that decides where you are going to work or is it the

government?

CS: It is the government. At the school they will prepare you.

JB: And do you like that way of the government doing it, or do you like it how we do it in America where everyone finds their own job their own way?

CS: I like the way the government does it over there, because here to find a job on your own is very difficult. Your application will remain on file. In the U.S. you are number 200 in line to get a job. But there you don’t waste time at all. By the time you graduate, your place is waiting for you.

JB: Do you elect your local officials, or how are the government officials chosen?

CS: Well the people elect them. The people choose them, because we all know the politicians around, so when it is election time, you vote for who you want, yeah.

JB: So do you know the politicians because you talk to each other and your

neighbors, or do they do advertising, like in America they do?

CS: Yeah they do advertising. Yeah, because not everybody knows who is who. Yeah.

JB: Tell me a little bit about the music and the culture.

CS: Okay, like I said earlier, every tribe has its culture. Every tribe has its music, like if I hear a music I know which tribe it is right away. And that’s how it goes. You know, but those are for entertainment purposes. Other than that they embrace both European music and American music because we have radio stations that play all the music around the world.

JB: One thing that I learned in a music-culture class is that the drumming in African music is different. So in American music we can usually count to three or four, but in African music they can usually count to ten or eleven.

CS: Yeah, that is the drum, and the drums are made traditional. It is not the drums that are made from Europe or America. They made it themselves, and they put it between their legs and they beat the drums with their, you know, hands, and so that’s how they come up with their own music. Yeah. But then as time went on people started to learn foreign music, to play trumpet, to play cornet, to play anything that is musical, piano. I grew up with my grandfather having three pianos in the living room, and when I’m practicing I will run my fingers through…glissando

sound. My mom would scream stop messing with the piano. So we have musicians in the family. My aunt married a man who is very good at playing the guitar, and one of his sons knows how to play piano. So, we have musicians in the family.

JB: So were there rural areas that were basically farming communities? And if so, what would people farm?

CS: Yes there are areas of farming communities. In fact when I was practicing midwifery, I was posted to a rural area where it is a completely farming community, and I was the midwife in charge of the clinic, so every Wednesday and Friday I held a clinic where the pregnant women would come and get their examinations and medications and everything. And I do delivery at the same time because the clinic was built in the way that it had everything that the midwife would need. You don’t have to travel miles to another hospital. So it was good. I enjoyed being there, but a rural area is a rural area! I got to the point where my children are growing and I want them to come to the city.

JB: And did you remember any of the things that they would farm in those areas?

CS: Oh they farm everything you can think of. Everything. Vegetables, I mean everything I see here, they grow it over there in abundance. And then they have animal husbandry too. Some go into goats and sheep and pigs and cows and all the feathery birds like turkeys and ducks and chickens. I mean everything,everything is there. Everything is there, but one thing I notice here… you have the slaughter house that slaughters the animals and brings them to the store. There you will buy it as it is and you go and do your own slaughtering.

JB: Do you do it at a slaughterhouse or do you do it at home, or where do you do it?

CS: Yeah, you slaughter it at home. You slaughter it at home. Except for the cow and the sheep and the goat and the pigs, the farmers themselves do the slaughtering and then they bring it to the market, but the city has inspectors who go and inspect that the meat is in good condition to sell to the people. And in fact, if you don’t go early, by 11:00 o’clock to 12:00 noon, everything is finished, because people are rushing to buy and to go home and cook.

JB: One time you said that over there they would say that Americans have no culture, and you told me about a dance they would do. Could you tell me more about that?

CS: Well, you know, because they have different tribes, they would look at each tribe’s culture to identify this person as his or her culture. Okay, here in America, all the 50 states have been put together, and they do everything the same way, that there’s no difference between Indiana and Denver, Colorado. When you see them they are all the same. But in Ghana when you see Ewe and you see Akan tribe, you can tell right away from the way they dress, and the way they speak. So we used to joke that Americans don’t have a culture. But that doesn’t mean that Americans don’t have a culture. And now that I have lived here so long I have found that every state has their own peculiar way of doing things.

JB: Awesome, and do they… how do they dress?

CS: They wrap the fabric around their waist and then they have a way of sewing the tuck… oh I forgot the name. They have it here. Sometime ago I saw some kind of design similar to that on top of a skein, and then they wrap their head with the same piece of the fabric and that’s how they dress. But now, they are wearing American dress. They are wearing American shoes. You wouldn’t believe they are now dressing their hair and putting rollers in and I was like oh my… these people are really into it now.

JB: And would the fabric be colorful usually?

CS: Yes. They have colorful fabrics. Each tribe has its own taste that they buy, so all the fabrics that are shipped into the country from Europe, they make the fabrics according to tribal taste. Yeah.

JB: And then the tribes, do they speak their own languages?

CS: Mm-hmm. I had to learn how to speak some of the languages because when I was posted to the rural area I speak Guan and that area doesn’t speak Guan, so I had to learn how to speak certain words to deal with a pregnant woman who is trying to tell me I want to drink water. I have to find somebody to Help…and ask, ‘what is she saying’? Then they will tell me, oh she said she wanted water. I’m like, oh, okay. But by and by I learned how to speak it, and then I will speak it,

and when I speak it they will laugh at me because I’m not familiar with the way it is real, but they understand what I’m trying to say.

JB: I don’t think it would be complete without asking about the spiritism and a little bit about the occult, the voodoo. Can you talk a little bit about that?

CS: Yes every tribe has its cult. Every tribe has its cult, but the Germans infiltrated into the country very early and started to preach Christianity. So that they wouldn’t stick to their culture in the cult things, so all of a sudden we have a Presbyterian Church. We have a Methodist Church. We have a Baptist Church. In fact one of my aunt’s husband was a pastor at the Baptist Church, and so I used to go to the Baptist Church on Sundays with my aunt because her husband was going to preach. Just to go singing and preaching. Then my grandfather grew up with the Presbyterian Mission House, the missionaries. He was a missionary boy and that’s where he met my grandmother whose father is German, so you know we do have both cultures in tribal, voodoo and all that. They still believe in those things, but they are changing. They are shifting to Christianity and God.

JB: So when you grew up it was more in the Christian environment?

CS: Oh yes. Our house was strictly Christian. You don’t come there with some kind of… my grandfather would tell you you don’t belong here.

JB: Now we need to bring it to an end. I just wanted to end it saying that one of the things that I noticed about you is that you are extremely intuitive, but you are also very smart. You are very smart in a Western sense. You have degrees.

CS: Yeah.

JB: And you have many skills. But I noticed that one time you said that you could smell that I was pregnant. That was amazing.

CS: Yeah, it’s because I did midwifery. When I see somebody, you know one of the sister’s daughters is pregnant and a couple of months ago she was fasting and I’m like, “are you pregnant?” And she said no. Why are you asking me, and I’m like well okay. And later on she came and said do you know that I was pregnant, and I’m like oh, okay. I can tell. I can tell from the color of the skin, from the face, you know, which you may not be noticing, but being a midwife, it is part of the training. You can tell when people are getting pregnant.

JB: Well I don’t think that that is taught in American midwifery to be honest.

CS: Yeah, they don’t have that, but we do because when you go to the rural area, there are some women who are pregnant and they don’t know they are. They just don’t know they are. I saw or they would say oh my stomach is just getting big. Oh I’m putting on weight. They don’t know it’s pregnancy, you know, so the government started to build clinics in the rural areas so we would help them to understand what it is to become pregnant and what to do when you are pregnant you know.

JB: So do you feel like the local politics actually took care of the people in like a

fatherly–motherly sense, like they are looking after people?

CS: The politics over there do not do that much. It is only school rather than go

into that. The politics there are into politics.So they don’t care about who is what and what is going on. But schools and hospitals and nurseries and midwives, we reach to the people. We reach out to them and we help them to understand.

JB: So in closing what is one of the things you miss about Ghana?

CS: Well, to tell you the truth I’m happy being here because it is so exciting. Every morning when I wake up I see something exciting. I see something that I want to see more and more and more, you know, so I don’t miss anything much over there. But now before I think, oh you need to come and see. We have developed. A lot of things are going on. If you come you wouldn’t believe you are in Africa, like oh really, you know. So my friend has 31 days to come and I will go and visit and come back, but now I feel like an American. Because I have been here very long, very long, so I have adopted an American lifestyle.

JB: Well I have loved getting to know you and having you as a friend Cay. Thank you so much and thanks for sharing about your homelife. I appreciate it so much.

CS: Thank you too for getting to know a little bit about Africa!

JB: Awesome!

CS: Bless you.

JB: Okay so we want to talk about tradition, authentic community life, so basically what is it like to be living in Argentina as a community. So what is your authentic community tradition? What is family life like, and then tell me about the different religions, and about the province. And also if you have any type of institute, like if you have elders or like how does your society direct itself? So those are the questions that we can use to start off with. Then if you want to talk more about another topic, that’s great.

JB: Okay so we want to talk about tradition, authentic community life, so basically what is it like to be living in Argentina as a community. So what is your authentic community tradition? What is family life like, and then tell me about the different religions, and about the province. And also if you have any type of institute, like if you have elders or like how does your society direct itself? So those are the questions that we can use to start off with. Then if you want to talk more about another topic, that’s great.  JB: So when you say friendshipness that means people are kind to each other?

JB: So when you say friendshipness that means people are kind to each other? JB: So you said families enjoy sitting out together in the evening. Do they usually eat a meal together in the evening and then enjoy being outside?

JB: So you said families enjoy sitting out together in the evening. Do they usually eat a meal together in the evening and then enjoy being outside?

TR: So they alternate.

TR: So they alternate. JB: Would you consider Argentina a poor country or a rich country?

JB: Would you consider Argentina a poor country or a rich country?

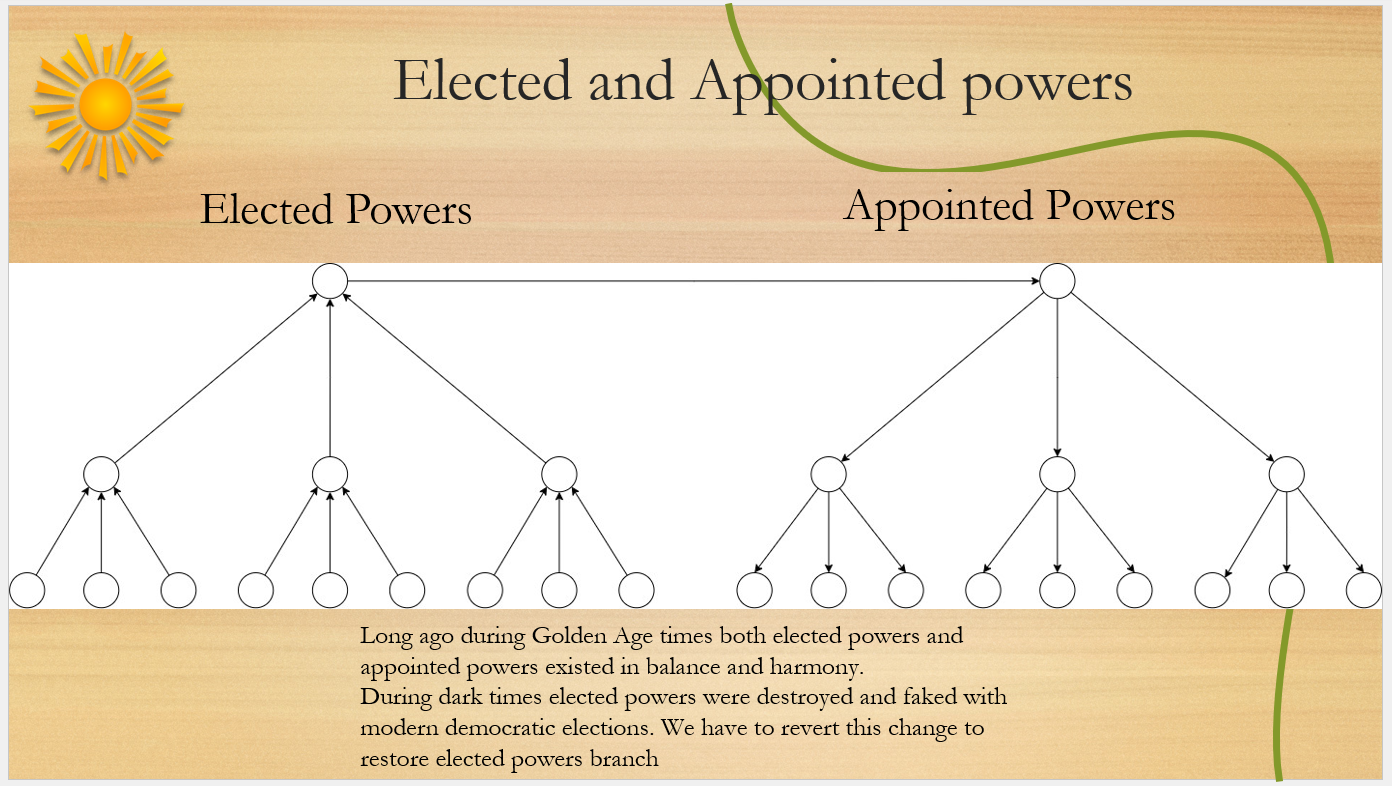

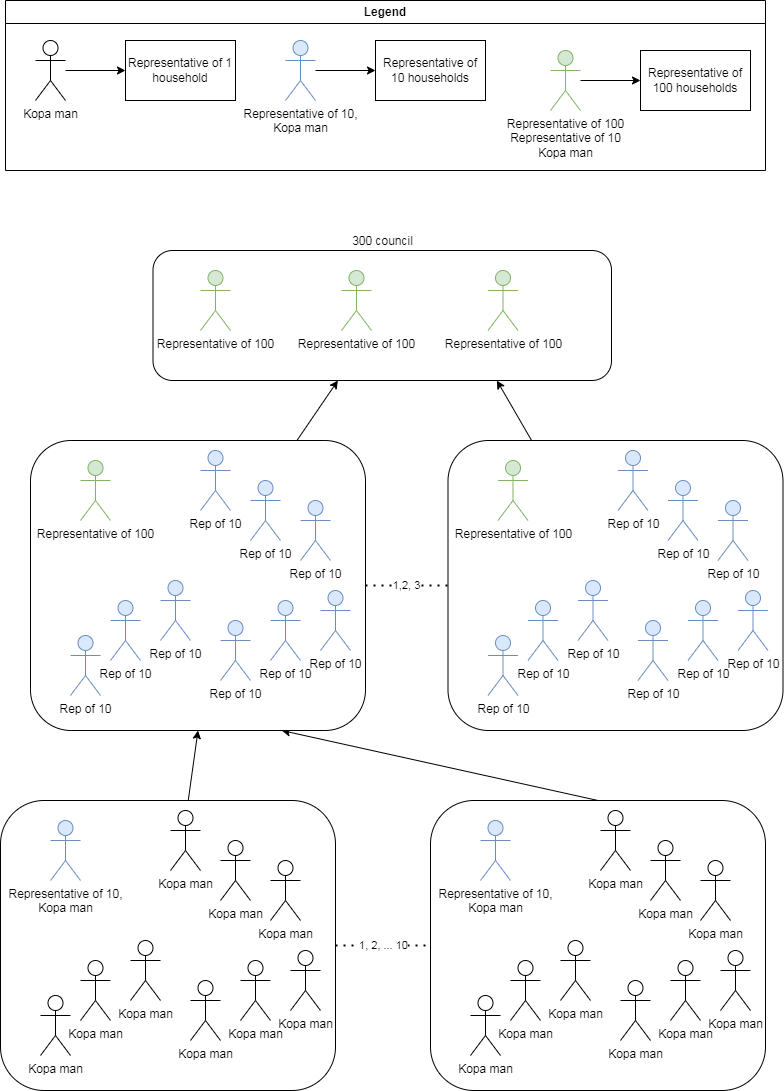

A Kopa man is a leader of his household. He is chosen as a mature man (50+ years) who is native by birth to the area he represents. He must have a grandson from his son (not from a daughter) to carry his family name. The man must be a head of the clan (the head of his family, his children and his grandchildren and their families), “rodan” in Rusian. “Rodan” this was the Kopa mature man, and all the rest were under him/report to him: brothers, sisters, women, and so on. A mature man must have his own household and provide for himself completely autonomously and independently, be a strong master.

A Kopa man is a leader of his household. He is chosen as a mature man (50+ years) who is native by birth to the area he represents. He must have a grandson from his son (not from a daughter) to carry his family name. The man must be a head of the clan (the head of his family, his children and his grandchildren and their families), “rodan” in Rusian. “Rodan” this was the Kopa mature man, and all the rest were under him/report to him: brothers, sisters, women, and so on. A mature man must have his own household and provide for himself completely autonomously and independently, be a strong master.

Direct Rule of the people — power, organised according to the principles of Veche/Kopa Law, solved the following tasks:

Direct Rule of the people — power, organised according to the principles of Veche/Kopa Law, solved the following tasks: